A review of talks and walks in 2019. These are in reverse order with the December talk first, working back to January.

“Then and Now: Plymouth Hoe, the Barbican and City Centreâ€

As members enjoyed their complimentary glass of wine and mince pies, Chris Robinson led a packed hall on an evening of nostalgia with his stunning images of Plymouth past and present.

He opened with scenes from the mid 1800’s showing an undeveloped Hoe, used previously for cattle grazing, the Trinity obelisk and west Hoe quarry. As the area became “gentrifiedâ€, it was not long before impressive terraced houses were built, along with the pier, a camera obscura and Smeaton’s Tower. Chris supplemented his images with many humorous anecdotes about the Beatles visit and how people used to pick up coins on the shore from slot machines after the pier was bombed in 1941.

Images followed showing Hoe Lodge, now a bowling club, the corrugated iron shed giving Tinside its name, an unspoilt Coxside, the coal wharf, old fish market and the police station. On the Barbican stood a line of black Ford cars but now a scene dominated by the new visitor centre. Another of his stories was of the police using an iron pole to fish drunks out of Sutton Harbour.

His Barbican images were full of stories; of the Dolphin Hotel where the Tolpuddle Martyrs stopped en route home from their experiences in Australia; the Queen’s Arms with its collection of 800 china pigs, and of course the famous Lenkiewicz mural, now in a sad state of neglect. Pictures of North Quay showed the old Co-Op, the Cooperage and fruit and veg stalls, the scene now however dominated by rows of expensive yachts. He mentioned how Stanley Gibbons sold his stamps from a shop in Lockyer Street.

The City centre inevitably because of WW2 showed the most changes. Memories filled the room as Chris displayed the old scenes, some of which were hand tinted prints: Turnbulls Garage (the first ever self service station outside of London), the burial yard, the old trams, the Guinness clock at Drake Circus, Spooners and C&A stores, the Rose & Crown pub and Old Town Street, one side completely demolished in 1937 as it was deemed too narrow.

More images of old Ebrington Street, part taken down to make way for trams, included Pophams store, the Corn Exchange, the Globe Hotel visited by Drake and later replaced by the Prudential building.

Chris’s final tale of the evening was about one of the survivors of the War – the Western Morning News façade. However, there was not so much luck for its neighbour Costers – incendiaries cleared off the WMN destroyed it! A glorious talk of old and new pictures highlighting the history of the city, only touched on by this brief summary.

“Not one of us: The Infamous and the Illustrious in Exeter, 1450 – 1950

In October, we welcomed Dr Todd Gray to give a talk about “Individuals set apart by choice, circumstances, crowds or the mob of Exeterâ€. From a series of stories over a period of 500 years, he gave a number of examples of the lives and peculiarities of people who did not fit into society and how they were treated:

Sammy Rowe, an elderly Cornishman with 150 convictions, liked prison. He kept on committing crimes so that he would be sent back to prison where he had spent most of his life. The judge finally said ‘that’s enough’ and sent him back to Falmouth where he died soon after. Sammy was a sort of celebrity but an eccentric.

In the 1770s, Sarah Frost went everywhere dressed as a man convincing everyone until she gave birth. It was such an event that it was in the newspapers at the time.

There was also an unknown Exonian in 1795 who lived in the city for 7 years and didn’t talk to anybody (apparently after saying the wrong thing to someone).

There were twins in Alphington who paraded around heavily rouged and in very bright clothes with their bloomers on show. The Victorians said that they had what we would call ‘mental health problems’. They were moneyed people and their grandmother was black and mother a mulatto.

In the 1880s Exeter City Council attacked the Salvation Army who were marching for temperance; thousands were arrested and this went on for 10 years. It was organised by ECC to get rid of those they didn’t like.

Mary Ann Ashford murdered her husband with arsenic in the 1860s. A hanging was a big event and people came from all over Devon to watch. Mary Ann put her foot on a plank to stop herself being hanged but the hangman knocked her foot away. The crowd became very excited, roaring as she died. Afterwards, her body was taken to Exeter hospital and dissected.

George Cudmore poisoned his wife in 1829 and after he was hanged for this his skin was removed and eventually used to cover a copy of the Poetical works of John Milton.

Elizabeth White was arrested for prostitution at 18; later she stole a hanky and was sentenced to transportation to Australia. No transport being available, after 2 years she was moved to London where she kept smashing glass in order to remain in prison The judge let her out and she died soon after.

There were the American conjoined twins, Millie and Christine, called the two-headed nightingale who travelled all round the world performing.

Twentieth century examples included entertainers who blackened their faces as a novelty and may have led to later popular programmes such as the Black and White Minstrel show.

These are just a few examples of stories told by Todd and to read more one would have to refer to his book recently published under the same name.

“Cotehele: an Antiquarian home of the Edgcumbe familyâ€

House and Collections Manager Nick Stokes led us through centuries of family history and development starting in 1353 with the marriage of Hilaria Cotehele and William Edgcumbe. Their house started with a slightly defensive but simple layout, remaining so until the arrival of Sir Richard Edgcumbe around 1450. Major changes and additions were made by him followed by his son Sir Piers in the 16th century.

Sir Piers subsequent marriage to Joan Durnford, whose family owned East and West Stonehouse (the latter then across the river in Cornwall), led to the building of Mount Edgcumbe house. Cotehele became a second home though a new tower was built along with brew, malt and count houses to support the local mining industry. By 1652 Colonel Piers, a staunch royalist who had fought in the English Civil War had moved into Cotehele, building the large wide staircase and other additions.

Further major changes took place around 1750 with the arrival of 1st Baron Richard Edgcumbe. He took on a complete remodelling of Mt. Edgcumbe and moved much of its contents to Cotehele including armour, clocks and tapestries. Encouraged by his friend Horace Walpole, then MP for the “rotten borough†of Callington, Richard began the period of antiquarianism – where things were made to look old and contents such as tapestries were cut to size to fit the rooms.

Rooms at Cotehele were kept small and intimate with an atmosphere of “gloomth†– gloomy and warm. This was continued by George, the 3rd Baron, who was then appointed the Earl of Mt. Edgcumbe in 1789. He carried out more reinvention with composites from different periods. Around this time King George 111 and his queen visited Cotehele and wrote articles of praise. By the mid 1800’s a guide book had been commissioned with superb illustrations and romantic scenes.

The links between the two houses continued through the 19th and early 20th centuries as the families occupied each in turn. At Cotehele, the whole east side was remodelled with butlers, housekeepers and servants quarters being added. Modern comforts were added along with more artefacts collections, landscaped gardens and parkland.

In 1941 Mt Edgcumbe was bombed and when the 5th Earl died in 1947 leaving his successor with a major problem, their 2nd home at Cotehele became the first property to be accepted by the Treasury in lieu of death duties. In 1974 it was acquired by the National Trust. Today it retains its dark and nostalgic view of the past, a Grade 1 listed building said to be one of the most complete and important Tudor houses in the country.

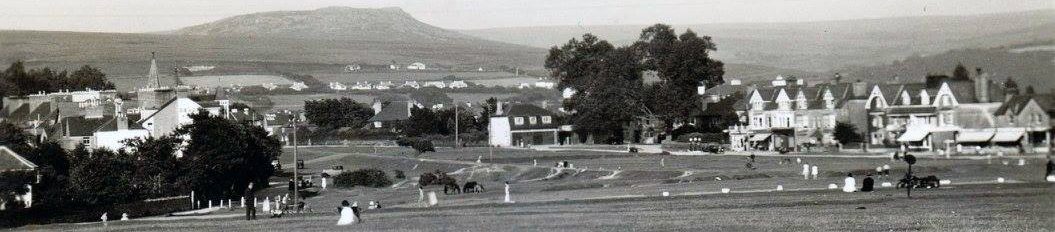

A Dartmoor Stroll on Walkhampton Common with Liz Miall

Our last outdoor event for the year was on a warm summer’s evening with Liz leading us on a path through time, just yards from Sharpitor car park. Without Liz’s expert guidance, many of the features passed along the way are easily missed.

The first example of this is a double stone row from the Bronze Age which abuts on the reave (ancient boundary), looking good in the evening sun, as it winds its way from Sharpitor across the main road to Leedon Tor. Close by is a fine example of a cist (grave) from the same period as the row.

Making our way downhill along a paved holloway, we reached the ancient ruins of Stanlake farm and hamlet. First mentioned in 1281 it was abandoned in the 1920’s, the Gill family being the last residents. Liz pointed out 3 longhouses, yards and gardens, cornditches, staddle stones and upturned troughs. Other pathways or strolls can be seen leading off to the surrounding small fields suggesting this was more than just a farm. The water supply was taken off the nearby Devonport leat.

We continued along the leat, built between 1793 and 1802, 28 miles long, taking its waters from the West Dart, Blackabrook and Cowsic to supply the town originally known as Dock. Its journey from 424 metres above sea level now ends in a waterfall emptying into the Burrator reservoir. Part way along the leat is the doll or Indian’s head. Originally thought to have been made by a French POW, it was vandalised in 1984 and then replaced in 1996 – though vandals seem to have struck again rendering it almost unrecognisable. At the base of the “Iron Bridge†aqueduct, the leat’s waters are supplemented by pipe from the River Meavy and Hart Tor brook, two of the pipes with 1915 marked on them.

At Black Tor falls are the remains of a crazing stone mill, tin mill, mortar stones and a wheel pit. A registration mark X111 can be seen on the mill lintel. Liz related a tale of how a colt of Mrs Gill’s became trapped in an old chimney and had to be released by Mr Pearce of nearby Kingsett Farm.

Our way back lay along the stone wall and cornditch below Black Tor. Once again a feature that’s easily missed is a 300 metre long stone row running adjacent to and sometimes embedding itself in the wall, with a possible burial cairn at the south end; just one of over 70 of its kind on Dartmoor which has the largest concentration of these monuments in Britain.

An easily accessible and enjoyable walk -history brought to life by Liz’s insights.

Chris Wordingham took time off from his duties as landlord of the local pub to lead a large group of members and friends around the extensive remains of this ancient copper mine. Though often hidden in the undergrowth, various features of the mine can still be seen. The remains form part of the huge complex known as Wheal Friendship, workings having been recorded as early as 1818, under a number of names up until 1922.

Devon United Mine which runs along the east bank of the River Tavy, was incorporated in 1901. Copper, tin and arsenic were soon discovered and sold and leats, tramlines, dressing plants and calciners were built. The site expanded with additional arsenic processing plant and production increased significantly in the early 1900’s. However, disputes and even legal battles with the neighbouring Wheal Friendship over the building of weirs and water extraction from the Tavy became common place putting a strain on the shareholders. This resulted in receivership in 1915.

In 1916 a fresh venture by a small private company began to explore further opportunities. Adits were extended and new ones opened and a lode known as Bennetts was explored. This was the scene of a tragic accident that year when a worker was injured in a blast and subsequently died of tetanus as a result of his injuries. Unfortunately when payable ore was finally discovered, a dispute with the local landowner prohibited further progress. The mine closed in 1922. Total ore sales over the period 1824-1919 were around £89,000.

Aided by Chris’s excellent handouts of the original mine layout, our walk took us along the edge of the surface workings of the area known as South Mine, the first item of interest being the old water turbine house which drove a compressor for air drills. We followed the pipeline up to the old take off from the original Cuddliptown mill leat, passing along the way various exploration tunnels which were used to chase the ore lodes, often unsuccessfully. The old smithy could also be seen near the river. Further up the path we were shown remains of the calciners, condensing chambers, shafts, wheel pits, an engine house, plus the old tram line and flat rod system. On its own at the far end stands the ruin of the old powder magazine store.

This is a fascinating area with extensive historical remains of these old mines hidden sadly beneath the vegetation growth and deserves more attention as a heritage site. Hopefully with people like Chris giving talks and leading such excellent walks will revive the interest and preserve their history for future generations to enjoy.

A guided tour of Okehampton Camp with Tony Clark

Starting off in the Officer’s Mess building, Camp Commandant Crispin d’Apice, backed up by Tony Clark, introduced us to the workings of the camp and a history of military training in the UK. He explained how our country has had a long history of defence and battles particularly during the Napoleonic wars in the 19th century. Further wars that followed increased the need for specialised training, particularly with the developments in artillery firepower.

At that time Dartmoor was still considered as a remote wasteland, but its wide open spaces, hilly and rugged terrain were thought to be ideal for mobile artillery which could fire over the hills and defeat entrenched enemy. Thomas Tyrwhitt certainly was in favour (£’s!) In 1873 after shrapnel had been invented, a huge training exercise involving over 12,000 men and 2,000 horses was held elsewhere on the moor. By 1875 permanent training had begun in earnest and the first structures appeared at Okehampton. Bell tents were erected on camping terraces, stables were built for over 400 horses, a hospital was constructed and sewage facilities created.

By 1892 the present military camp had been built. More permanent buildings were constructed replacing the earlier more temporary structures. These have been added to significantly over the years with more modern facilities being added such as showers, food preparation areas and en suite accommodation, though several of the originals still remain. During WW1 tracked vehicles were used, live firing with mortars continued and more buildings were constructed and updated for WW2 training. The camp has been used for Dunkirk evacuees, POW’s and Falkland War preparations.

Our visit continued with a tour of the site entering many of the numerous buildings, many of which are original and listed such as no. 69, the Warrant Officer’s and Staff Sergeant’s Quarters from 1894. Many of the buildings have original corrugated iron roofs and among those seen were stables, decontamination block, gun store, gun maintenance, toilet blocks, farrier’s facility, married quarters and the guardhouse. We finished in the superb museum which has an amazing collection of artefacts ranging from old photos, military shells and equipment, badges, pencils etc.

The Camp is now the 2nd oldest training area in the UK. The special qualities of the moor support the modern training methods which take place on 3 ranges with safety and conservation being key objectives. Lighter weapons are used with no artillery, tanks or mortars. Static targets are used at Wilsworthy and the other areas support some live firing and dry training with blanks. Other activities include route marches, rock climbing, mountain biking and team building.

The History of the Plymouth Royal Navy Dockyard

Commander Charles Crichton’s slide show with his highly entertaining anecdotes produced a colourful talk on the development of the Dockyard from the late 17th century. Plymouth already had a naval reputation mainly due to Drake but it was William of Orange who recognised that the country needed a bigger shipbuilding facility and naval base. After several sites were considered in the locality, the area known then as Dock was chosen in 1690.

A stone lined basin and first ever stepped dry dock were built in 1692 along with a centralised storage area. Other buildings designed by the navy architect Edmund Drummer included a double ropery and a grand terrace of houses for senior officers, most of which was destroyed in the Blitz.

A huge period of expansion started in the mid 18th century with the development of South Yard. Additional slipways (one still survives unaltered today), dry docks and wet basins were established for the repair and maintenance of the fleet. Workshops, a new ropery, smithery and sawmill followed and the Yard still contains several scheduled monuments and listed buildings from that period despite the war damage.

A new gun wharf named Morice Yard was added which was a self-contained establishment with its own complex of workshops, offices and storehouses including on-site storage of gunpowder. Further expansion followed in the 19th century with the advent of steam power and the opening of North Yard at Keyham, linked to the other yards by underground tunnel and rail lines. In addition to more docks and basins there were specialised workshops, foundries and forges. An engineering college and the HMS Drake Barracks were built. The town of Dock was renamed Devonport in 1823.

The dockyard in the 20th century doubled in size with over 18, 000 employees and over 300 ships built. Additional facilities and modernisations followed including the frigate complex, nuclear submarine, Royal Marine and amphibious warfare ships’ bases.

The Dockyard today is run by Babcock employing less than 3,000 service personnel but still probably the biggest naval base in Western Europe. Parts of South Yard are now used for the building of superyachts and as a marine industries hub together with the Heritage Centre maritime museum. A fibre replica of the “King Billy†ship’s figurehead stands at Mutton Cove.

Commander Crichton’s haunting tales of paranormal activities around a rumoured execution cell in the old ropery rounded off an entertaining evening.

“Life on Dartmoor in WWIâ€

Peter Mason’s talk through his use of letters, reminiscences and excellent images of people who lived in this period brought to life what was happening in those difficult times. Before the war tourism was flourishing, farming was recovering from depression but there was widespread industrial unrest. Emily Pankhurst was imprisoned in Exeter. Flower and agricultural shows were still in progress when war broke out.

Military training started on the moor and young men flocked to join in the adventure – work on Castle Drogo stopped. Reservists were called up, horses requisitioned and amidst concerns about German spies ex poachers were recruited to stand guard. As initial enthusiasm for joining up to fight waned, recruitment marches were held across the country and many Dartmoor farmers held back. Letters read by Peter from anxious relatives emphasised the concerns with an increase in conscientious objectors.

However, many schemes started to help the war effort and lots of locals were involved in fund raising events and the collection and processing of Sphagnum moss and foxglove leaves for wound dressings and pain relief. There were egg collection schemes, plus berries and conkers for use in cordite. Voluntary aid departments were set up across the moor and visits arranged to tend the returning wounded, even the Scouts were involved in providing teas and entertainment.

The demand for timber for pit props in the trenches brought in workers including some of the conscientious objectors (the “Devon Knutsâ€) and others were brought into help with farming. 1916 also saw the birth of the Women’s Land Army who were trained at Seale Hayne and taught to plough, milk cows and drive tractors and other vehicles. Even prisoners of war were roped into help. Peter’s extracts from the memoirs of Cecil Torr and the suffragette Olive Hockin highlighted their involvement.

Life continued as normal where at all possible despite the impact on schools of epidemics of mumps, chicken pox and measles. Scouts ran messages, Lustleigh May Day carried on and other social events continued to support the war effort.

When the war ended in 1918 church bells rang again and detonators set off on the rail line into Lustleigh welcomed the home-comers. Armistice dinners were held (men only!). Empire Day was held in Ashburton in May 1919. The establishment of war memorials started to much discussion and controversy. The North Bovey lychgate was dedicated on the 10th Jan 1920, the official date of the WW1 Peace Treaty.

“Morwellham: Tavistock’s Portâ€

Rick Stewart started off by emphasising the correct pronunciation of this settlement, the highest navigable point on the River Tamar. Benefitting from being on flat land it was probably used by the Romans from the nearby Calstock fort, growing further from the influence of Tavistock Abbey, and again from the 13th century onwards as tin mining on Dartmoor increased the river trade.

Following the dissolution of the monasteries in 1538, the land was granted to the Duke of Bedford but it was rich men from Bristol that had the biggest influence on the development of the port by the 18th century. These men were traders who used slave monies to develop copper mines, smelting plants and factories in the Bristol area. When copper was discovered in the Tamar Valley and was easier to extract, their attentions and money moved south and the port experienced a period of boom and bust as the industry took off.

The opening of the Tavistock canal in 1817 increased the flow of goods to and from the port and then in the 1840’s the richest copper lode in the world was discovered and the mine of Devon Great Consols opened. This created a huge mining boom with £1 shares trading at £800 a few years later and a massive increase in trade through the port. A 4.5 mile long railway was built in 1858 connecting to the port by an incline tramway and the building of the Great Dock doubled the port’s size. The Duke of Bedford built cottages for the miners, Tavistock was thriving and these were peak times.

However, competition from Chile where opencast mining was cheaper led to a need to diversify and by the 1870’s the copper mine was now the largest producer of arsenic in the world, exporting this via the port to the US in huge quantities for use as an insecticide in the cotton fields . By 1905 this trade had ceased and the big mine closed and the port and quays fell into disuse.

Increased leisure time and interest in history and industrial archaeology grew in the mid 20th century and in the 1970’s restoration work began on the area. A charitable trust was set up to start an open air museum, the old George and Charlotte mine was re-opened and the Great Dock refurbished. The mid 1990’s recession led to further setbacks but the awarding of Unesco World Heritage Site status to the area gave a further boost to the port.

Today, it is owned by private enterprise and its fascinating history lives on for all to see.

“Tavistock Canal and its Historyâ€

Simon Dell kicked off our 2019 programme with an historical stroll along the canal and a brief history of the man responsible for its construction, the mining engineer John Taylor.

Taylor had made his name in the late 18th century as the mine captain of the Wheal Friendship complex in Mary Tavy, at the time the largest copper mine in the world and a major exporter of arsenic to the US for the control of the boll weevil.. Transporting of the ores by packhorse to the port of Morwellham was a real problem so Taylor came up with the idea of a canal and an Act of Parliament was passed in 1803 to enable work to begin.

Initially using part of the old Crowndale Farm leat the canal took 14 years to complete over a distance of 4.5 miles. It flowed gently downhill along most of the way, negotiating 3 copper lodes with 24 waterwheels en route and required a 1.5 mile long tunnel. It was then connected to the port by means of an incline tramway. 38ft long wrought iron tug boats drawn by horses carried the ore down the canal bringing back grain, lime and coal. The ore was shipped to South Wales for smelting.

Simon’s talk took us on a virtual journey along the canal starting at the take off point below Abbey Weir with its iconic leaf clearer! The canal flows under the old town grain store (now the Guide Hall) past the old Wharf offices and coal store through the Meadows and out of the town into the woodland beyond. It continues under an arched bridge stained blue with copper residue, over an aqueduct until it reaches Lumbur Bends with its lockgate and the amazing tunnel construction.

An embankment formed from the tunnel excavations stands over a 0.5 mile incline to the copper lodes of Wheal Crebor mine with its own waterwheel. The tunnel passes underneath, extremely narrow with adits leading off, the walls coloured by yellow ochre. Standing in the field above are 3 8ft high air shafts which plunge 350ft vertically underground. It took the barges 2 hrs to negotiate the tunnel downstream and 3 hours back.

In 1819 a branch of the canal called the Collateral Cut took a route up to the slate quarries at Mill Hill, with an accompanying horse drawn tramway. Although traces of this can still be found, much of it is on private property.

Since 1933 the canal has been utilised by the hydro-electric Morwellham Power Station, connected by pipeline. Today, the canal because of its importance in mining and transportation history forms part of the Cornwall and West Devon World Heritage Site.

END