“The Tavistock Trendle”

Although an official scheduled monument, this 1.6metre high earthwork with shallow ditch, situated in the grounds of Mount Kelly is not well known. Andrew Thompson explained how recent research has revealed more information but also a history of speculation about its origin and purpose. Andrew’s objectives had been to review these previous theories and determine its future management. It is classed as a hill slope enclosure, located on a valley spur, close to the Walla Brook and is not a hill fort.

On the Bedford Estate map of 1768, it is shown as “Little Field†with another feature on the opposite side of Old Exeter Road marked as “Higher Trendleâ€. Regular updates of these rental maps show various changes. The OS map of 1883 records the site as “Camp†with a flagstaff also shown. By 1905 OS show the railway line cutting through with only a small piece marked above the old road.

Andrew then reviewed early written records. In the early 17th century, the Bedford papers mention trendles with Trendle Meadow recorded later in the century. Rachel Adams in her 1846 book, mentions an enclosure in a series of walks from Tavistock to Mary Tavy. The renowned Dartmoor author RH Worth in 1889 says that it was known by locals as “Roman Campâ€, an original site for Tavistock. He goes on to say that it was late Celtic (Iron Age) supported further by the discovery of a socketed axe in 1947. He also claimed that it was part of the ancient routeway known as the Grand Central Trackway, also part of the Fosse Way. Around the same time, another eminent writer, Robert Burnard, suggested his excavation of a nearby reave was part of this trackway, though Andrew Fleming in the 1960’s proved that reaves were in fact prehistoric field boundaries. Later excavations in the 1960’s revealed evidence of bank slippage (possibly after its abandonment) and the discovery of pottery fragments dating from the late Iron Age period.

A trendle is generally thought to mean “a round place†though our trendle is more of an hourglass shape, its southwestern boundary having been encroached on by staff houses and a leylandii hedge. In more recent times, LIDAR and geo-physical surveys have produced some interesting details such as banks and ditches, plus three round features, which if they are actual round houses (dwellings) raises more questions about the site’s status and purpose. At nearby Taviton, there is also a very clear round feature – could this be the real Trendle?

Research into this fascinating site continues and a much more detailed article on this subject by Andrew and John Hudswell can be found in the Report and Transactions of the Devonshire Association 2020.

“Arsenic in the Tamar Valleyâ€

The image of arsenic in the 19th century was associated with poisoning and murder. It was easily accessible and as a white powder sometimes confused disastrously with flour. Wrapping it in purple was one solution.

Rick Stewart in his new talk explained its other more acceptable uses: as a pesticide (rats), insecticide (fly papers, controlling the Colorado beetle and the Boll Weevil in the US in the potato and cotton fields), sheep dipping in Australia, wallpaper dyes, cosmetics (soap) and lead shot – amongst others.

By the mid 1800’s the huge copper mine at Devon Great Consols (DGC) was in decline and the production of arsenic took over. By 1870 it had become the biggest producer in the world with enough arsenic to kill the entire planet! Several associated mines also opened in the area such as those at Gawton with its famous bent chimney (still standing) and the longest flue in the UK and Greenhill at Gunnislake.

Rick went on to describe the various equipment and processes in its manufacture. Starting as Arsenopyrite – a waste product from copper – it had to go through stages of roasting and refining. William Brunton was a major player here with his invention of the calciner consisting of a feed hopper, rotating oven and fire box. The alternative Oxland tube was also in use at DGC. The roasting process took fumes up a flue where the material cooled and condensed and deposited on the walls as soot (one sixth of a teaspoon was said to be fatal). Waterfall chambers restricted the sulphur dioxide emissions. A refining process with clean fuel was required using separate chambers where at the end of the burn, workers (mostly male) shovelled the powder out in wheelbarrows. A third refining was required for pharmaceutical grade. From there it was ground and packed into barrels and sold to merchants.

Rick’s images highlighted the dangerous conditions as workers took few precautions wearing only a bandana and sleeveless shirts. Exposure led to both acute and chronic conditions such as TB, cancer, heart and nervous system problems, and skin lesions. Medical reports are hard to come by, but one specific example of Rick’s research showed a worker who had shown various symptoms in eighteen of the 19 years working at the mine. A belated Act in 1892 did improve workers’ conditions as the Duke of Bedford and other landowners became more safety conscious.

The mine at DGC closed for full scale arsenic production in 1902, the sheep blight in Australia being a significant factor along with the creation of synthetic solutions to industry’s requirements. There was some further small-scale production in the early 20th century particularly in the demand for bullets in WW1.

Another fascinating talk from Rick Stewart rounded off at the end with many questions and more interesting discussion with a lively audience.

A Guided walk at Morwellham

Gathered under umbrellas in the misty rain was an unusual experience for those veterans of our outdoor events, but spirits were not dampened and the conditions added to the atmosphere as Rick Stewart guided us around the old historic port.

Once part of Morwell Manor, its name (with the emphasis on Ham) probably means “flat area by the river;†the Tamar, a transport artery since about 1290. An area rich in minerals it was almost certainly used by the Romans, given the proximity of the fort at Calstock. In the early years, tin, lead and silver passed through the port.

Following the dissolution of the monasteries in the 16th century, the lands passed from Tavistock Abbey ownership to the Dukes of Bedford and later the Gill family proceeded to develop the port. Copper was soon discovered nearby and the ore exported to Swansea for smelting.

By the 19th century the mines around Mary Tavy were in full production followed by the huge Devon Great Consols (DGC) copper and later arsenic mine and the George and Charlotte mine at New Quay. The port during this period was said to be one of the richest in the Empire. Because of the poor roads the Tavistock canal was built over a period of 14 years, opening in 1817, iron barges carrying minerals and goods such as slate and limestone to and from the port. It passed through a 1.5mile long tunnel and the Wheal Crebor mine.

Access to the quays some 250ft below was via an inclined plane and Rick’s walk took us up steeply through the woods to “Incline Cottageâ€, the canal terminus. He explained how a sophisticated counterbalanced process controlled different weights of materials using a large waterwheel. DGC with its own foundry required a separate railway incline to the quays and other tramways criss-cross the site. Further along the canal we followed a deep leat built to convey water to the settling pond of the HEP station, opened in the 1930’s. Manganese was another mineral discovered in the area and Rick explained how the large waterwheel on the quay that was used in its processing was supplied by a leat on stilts from the canal. Water usage was fully exploited all over the site including the farm where another waterwheel powered a threshing machine.

At its height in the 19th century there was a big influx of miners and workers and serious overcrowding led to the old malthouse being converted to a barracks and the building of the model cottages in 1856.

However, by the mid-19th century the copper industry was in decline as deeper mines became more expensive to exploit and imports were cheaper. Arsenic and horticulture kept the port going but when DGC finally closed in 1906, its usefulness was ended. Now a living museum, this is still a fascinating area to explore.

Our visit ended with a welcome pint in the port’s very own Ship Inn. A superb evening in the company of Rick Stewart whose knowledge and easy style of presentation was enjoyed by all.

A Guided Walk around Challacombe Farm

Nestled in the valley below mighty Hameldon and the historic Bronze age village of Grimspound, the Duchy farm of around 180 hectares has a long history with evidence of medieval strip fields (lynchets) and archaeological features from the tin mining industry plus stone rows and hut circles. It is managed organically today by Mark Owen and Naomi Oakley as a regenerative farm that puts nature first, producing high quality, animal welfare certified 100% grass / pasture fed beef and lamb. It is a SSSI and County Wildlife site.

On a sunny evening in July, Mark showed us around the beautiful landscape, explaining how they work to improve the land by working closely with nature and their animals whilst also actively encouraging the public to explore the area – there are numerous footpaths running through the farm.

The immediate area close to the farmhouse has remains of several medieval houses, including one with features of a Dartmoor longhouse. Some of these buildings were still in use up to 1880, one becoming a cider house serving thirsty miners from the nearby tin mines and it is probable that most inhabitants here combined farming with mining to make a living from the land.

Mark led us out onto the common where many of his 200 sheep and 30 cows (North Devons and Welsh Blacks), plus one bull graze on the environmentally sensitive land, including Rhôs pastures (enclosed species-rich purple moor-grass and rush). He explained the process of mob grazing where the animals are moved around to avoid over grazing in one area, reducing negative impacts of the herd on the land.

Clambering down through the bracken, we came upon one of the relics of tin mining in the shape of a leat, wheel pit and nearby buddles, very overgrown. Close by were other more recent remains, a rusting piece of farm machinery. Further research suggests this was an ancient mower.

Coming back closer to the farmhouse, we passed the pond with its natural filtration system (a habitat award in 2005), house martins darting overhead and dragonflies skimming the surface. Alongside the pond is a 13th century tinners mouldstone.

We entered one of the several hay meadows which are open to the public for a couple of weeks during the summer. We were too late to catch the main displays of the wildflowers including various orchids but dwelt amongst the grasses and hay rattle, while Mark explained the process of the traditional hedge laying techniques carried out in these fields.

On our way back we passed by the Rhôs pastures alongside “mile straight.†Orchids and bog asphodel abound here, where on a good day can be seen the beautiful marsh fritillary butterflies. Over the bridge back to the carpark, we said hello to the troll! Several members then took advantage of taking home some of the farm’s organic meat. Thanks to Mark for an interesting tour – their farm and the way it is managed is a shing example of how farming and wildlife can co-exist successfully.

A Stroll along the River Tamar at the ancient port of Calstock

On a beautifully warm and sunny June evening Steve Docksey took a large group of us along the River Tamar at Calstock. The walk began in the car park, originally a marsh in 1815, though by 1841 a small copper ore yard on the west side, owned by the Williams family with the east of the area still a marsh. By the 1860s the yard had been leased to Vivian and Sons of Swansea; the whole area then one yard and still covered in the original cobbles. Copper ore comes in bulk needing lots of fuel to smelt, so it was transported to South Wales, the land of coal. The East Cornwall mineral railway (ECMR), 3’ 6†gauge, passed to the south of the Tamar Inn bringing ore to the quay.

From 1066 to 1806, the manor changed hands several times including the Valletorts of Trematon, Richard, Earl of Cornwall, and the Duchy before being sold to John Williams in 1806; it was dissolved in 1926. The Tamar Inn changed its name from the Waterman’s Arms in the late 18th century, to the Boatman’s Arms in 1827 and back to the Tamar in 1850 with various proprietors. The inn, one of 33 recorded in the parish, was also used for manorial court meetings.

Steve told us that there are 9 lime kilns in the parish being a major industry in the 19th century and transported to Kelly Bray by the ECMR. We stopped at Doidge’s kilns; a very large structure built into the hill where archaeological work has been done in recent times.

Further along the river we came to the old ferry crossing, thought to date from Saxon times. It was owned by the Earl of Mount Edgcumbe, but the rights were leased to various individuals. In 1945 it was handed over to St Germans and Tavistock RDCs but closed in 1967.

Another building known as the Navy and then the Commercial also held manorial courts. Listed in 1818, it was known as Commercial Hotel by the early 1900s but had closed by WW1.

There were once 31 chapels in the parish, including 7 non-conformist chapels in Calstock town. We passed by the United Methodist church which was opened on Church hill in 1856 and enlarged in 1859.

Steve pointed out Goss’s boatyard where James Goss and later Edward Brooming built barges, cutters, smacks and paddle steamers. The whole area was opened up by Lord Ashburton in 1851, no buildings along this area up until then. The Steam Packet Hotel opened in 1852 but closed in 1950s. River excursions along the Tamar became very popular and large numbers of boats were built for the purpose by several different companies.

The ECMR was opened in 1872 to connect mines and quarries in East Cornwall with the quay at Calstock where a rope-worked 1 in 6 incline for wagons with goods were brought down to river level. Following the opening of the LSWR connecting line to Calstock a hoist lifted wagons to the top of the new viaduct.

The walk ended at Kelly Quay, now Kingfisher Quay, where the Ashburton Hotel had been built as a fishing lodge in the late 1850s. It became the Danescombe hotel and was closed in the 1990s – now a private dwelling.

Steve Docksey was thanked for a remarkably interesting and informative walk/talk.

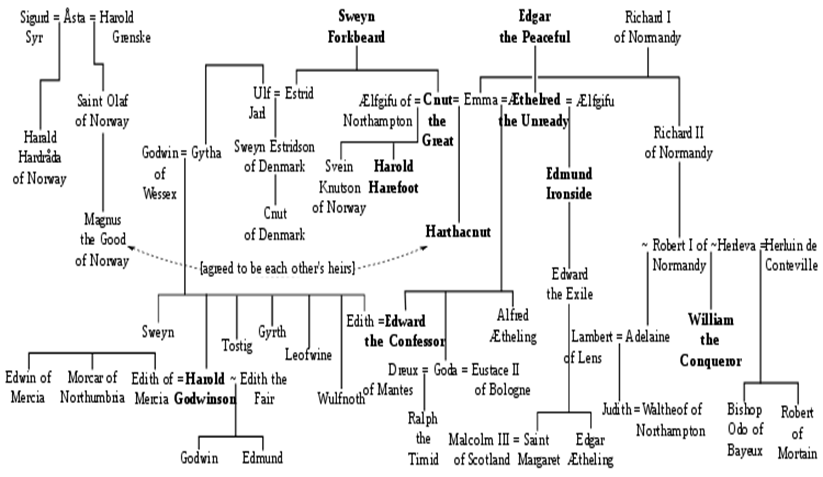

The Last Years of Anglo-Saxon England 1000-1066AD

In the year 1002AD Aethelred the Unready was King and married to Emma of Normandy. This marriage was intended to bring unity against the Viking threats which often came from Normandy. But less than 9 months after his marriage, Aethelred ‘s order to kill all Danish people who lived in England was shocking as most Danes were living peacefully alongside the Anglo Saxons. Sweyn Forkbeard, King of Denmark soon sought vengeance and a renewed Viking onslaught was experienced in the following years.

By 1006 a large Viking force was ravaging over large areas of southern England and Sweyn took control of England in 1013, declaring himself king, Aethelred fled to Normandy with his wife and their two sons, Alfred and Edward.

When Sweyn died in 1014, Aethelred returned to England with his family and led a force to drive Sweyn’s son, Cnut, out of England. But Cnut returned in 1015 and there were several battles with Aethelred ‘s other son, Edmund Ironside. When Aethelred and then Edmund died in 1016, Cnut was accepted as King of England (and Denmark) and married Emma, giving her power and status once again. Emma’s first child with Cnut was a son called Harthacnut.

One Anglo Saxon, Earl Godwine achieved great favour from Cnut with lands and office as Earl of Wessex and married Cnut’s daughter Gytha. Peace reigned for a while. When Cnut finally returned to England after battles in Scandinavia, his son Harthacnut remained as King of Denmark.

In 1035 Cnut died at the early age of 38 leaving Emma in a very vulnerable position as he had not named his successor. He had left sons from his two marriages, the eldest Harald Harefoot and Harthacnut. Cnut’s first wife promoted her son, Harold as the new king, rallying support, whilst Harthacnut, under pressure from Magnus, King of Norway, decided that he had to stay in Denmark.

At this point, Emma turned to her own sons Edward and Alfred, but Alfred was murdered. In 1037 Harald was chosen as King over all England. Earl Godwine was now back in favour and remained as Earl of Wessex whilst Edward fled back to Normandy.

Emma’s fortunes plummeted and she was forced into exile. When Harald Harefoot died in 1040, Harthacnut was proclaimed King of England. However, he proved to be an unpopular leader and died suddenly in 1042 with Emma’s son Edward (the Confessor) becoming King in 1043.

Godwine died in 1053, and his eldest son Harold Godwineson succeeded to his father’s estates controlling most of England.

When Edward the Confessor died on 5 January 1066, there were a number of claimants to his throne. One, Edward the Exile, the grandson of Aethelred died before he even had a chance to meet King Edward. Harold Hardrada, King of Norway in 1066, felt that he had a right to succeed and invaded England in September 1066. Add in Harold Godwineson and William of Normandy who both thought they had been promised the throne by Edward. What happened next could be Alan’s next talk!

This was a riveting talk by Alan Bricknell, his skilful and entertaining use of a complicated family tree chart, keeping the audience fully absorbed.

The History of Mount Batten

We attended a very entertaining, interesting and illustrated talk on the History of Mount Batten which included lots of stories and jokes throughout.

Robin Blythe-Lord explained that the peninsula of Mount Batten lay on the east side of Plymouth Sound and is the site of the earliest port. It was originally called How Stert which is Saxon meaning ‘high ground’ and there is evidence of Neolithic habitation. In the Bronze Age tin and lead from Dartmoor were transported down the Plym to Cattewater. Iron Age coins and horse harnesses have been found and there is evidence of thatched round houses. In Roman times it was an important port, possibly the lost port of Tamaris. In the 16th century there was pirate activity, boat maintenance and fishing. An armed merchantman was found in the Cattewater from around 1530.

In the seventeenth century it became a mass grave for victims of the plague and during the Civil War the area was used for burying the dead. In 1666 after the Restoration the tower was built as part of the Plymouth defences and was named after the governor, Vice Admiral William Batten. The tower is hollow and has a flat roof for the positioning of cannons, facing seaward and landward. Inside there were 2 floors, the ground was for storage and the garrison occupied the other floors. When the Citadel was completed the cannons were moved there.

The area was used for burials again during the cholera epidemic of 1832-1849. When the Castle Inn was being built they dug up some of the plague victims. Lots of artefacts were also found and stored for safekeeping in Plymouth but, unfortunately, were all destroyed in the Blitz. From 1878 to 1881 the breakwater was built for protection of the Sound.

In 1910 people caught the ferry to Mount Batten and spent time on the beach. In 1911 sea planes were trialled there and the breakwater had to be altered for the planes to land. In 1917 the hangars were built which are now listed. In 1918 the first Wrens arrived and in 1919 the first transatlantic flight went from Mount Batten. In 1929 the Met office was situated at Breakwater House and the instruments were kept in the tower. In the 1920s the government bought Mount Batten but had to pay compensation of £24,000 to the previous owner, Earl Morley, who had the mineral rights.

T.E. Lawrence was stationed at Mount Batten and witnessed an air crash in 1931; due to the slowness of rescue boats he designed a much faster vessel for rescues. In WW2 Shorts Sunderland flying boats of the RAAF operated there and Robin showed photos of the damage done by German bombers. In 1984 the government announced closure of RAF Mount Batten: local amateur archaeologist and Barry Cunliffe of Oxford University arranged a dig to find the artefacts which are now in the museum. In 1993 the area was handed over to Plymouth Development Corporation and is now home to a Sailing and Water Sports centre with some housing; no more building is allowed. Mount Batten is also used for the annual National Fireworks display.

New Zealand- Plymouth connections

Clive Charlton’s brand-new talk took us to the settlement of New Plymouth on North Island in New Zealand. For centuries occupied by quite sophisticated Maori tribes, “Taranaki†(named after the local volcano), from the 1800’s started seeing early pioneers such as whalers and sealers, and traders looking for flax, metal and even guns.

One of these was Richard “Dickie†Barrett who set up the first trading post and married a local Maori, a key link to future settlement. He also negotiated land buys of dubious legality, helped by lots of land being unoccupied with many of the true owners absent because of slavery and warfare. He learnt the local language and even fought in inter-tribal conflicts.

As colonisation pressures started to grow, the Treaty of Waitangi was signed in 1840, a constitutional document between the British Crown and the Maori’s, aiming to protect the local culture and equality. The Plymouth Company of New Zealand was set up and with the Southwest of England going through a period of rural depression, a new life overseas seemed attractive and was encouraged. The company surveyor named Carrington was sent out to map out the area for the new settlement.

Migrant families from all over Devon and Cornwall, even 7 from Meavy, could travel free, though the 3-month voyage from Plymouth was difficult. Life once there was also harsh, with rough living conditions, food shortages, boredom and drunkenness leading to growing unrest and conflict. Numbers arriving in the congested area grew to over 1,000 by 1843. The press referred to the colonisation process as “heroic workâ€.

A prominent artist called Edwin Harris from Newlyn took his young family to settle in the new town in 1840. His daughter became the first professional artist, producing books on local flora and fauna. Many of Edwin’s own paintings survive in the town’s Puke Ariki Museum.

As the town of New Plymouth continued to grow, so did local Maori resentment, resulting in 1860 the start of a year-long armed conflict on land ownership and sovereignty known as the Taranaki Wars. The town was transformed into a fortified garrison and troops poured in; there were many casualties on both sides. William Odgers, a Royal Navy sailor and one-time Saltash innkeeper was awarded the Victoria Cross for his gallantry before the wars ended in an uneasy truce.

Taranaki today is known as a vibrant and contemporary city, famed for its sunny climate, art galleries, picturesque parks, decadent dining, and family-friendly fun. Many of the places and street names echo their origins from our own city of Plymouth.

Clive concluded his talk with the sad tale of the connection to Bere Ferrers. In 1917, ten soldiers from New Zealand alighted from their troop train on the wrong side, having assumed they should leave by the same side they had entered, and were struck and killed by an oncoming express. A plaque to their memory was unveiled in 2001 in the village centre. A big thank you, once again to Clive for stepping in at late notice with his excellent talk.

The Railway Time Machine

A goodly audience was entertained by Bernard Mill’s photographic time machine, which took us on a nostalgic journey around the local area. Using familiar landmarks, Bernard’s camera captured the changing landscapes as the railways gradually disappeared, often without trace. Contrast these two pictures taken from the same place, several years apart near Monksmead, Tavistock.

Churches provide key points of reference as seen above at Monksmead in Tavistock, illustrating the way history can be easily erased. Dual carriageway and housing dominate the scene in St. Budeaux where railway lines once passed through. The viaduct at Keyham creek was another example with housing replacing the Southern line, though the GWR survives. Car parks and retail developments contrast with views of the inner-city lines, with a background of old landmarks such as the dockyard grain silo, various churches, Plymstock power station (Bernard includes a video of the chimneys being demolished), and also on the scene are old vehicles like Scammel trucks and Millbay laundry vans.

Crossing into Cornwall, Bernard captured images of the old Saltash steam ferry from 1961, a “steam special†crossing the bridge and the fireworks display on its 150th anniversary. Of particular interest and pride were his photos of the wooden steam rail coach with boiler beside the river on the Looe Valley line; stunning images captured on a clear day by the Moorswater canal bridge, with frost on the fields, still waters and steam smoke in the air. More memories came with scenes of the vintage locomotive “The City of Truro†back at its home, Bernard pleased to have taken photos from the bell tower of the cathedral.

Back nearer home, we visited the Plym Valley railway, a rare example of a restored line. A founder member of the society, Bernard took us past the old Lee Moor tramway crossing and up to the current terminus of the rebuilt Plymbridge Halt platform – the old one now being at St. Ives station. On up what is now the cycleway, past Shaugh Bridge Halt and its once impressive rhododendrons and Clearbrook with its derelict railings the only trace of lines past. At Yelverton, a lovely image shows locomotive no. 4538 coming out of the station. In 1962, the footbridge and signal box were still to be seen, but the area, including the start of the branch line to Princetown is now sadly totally overgrown – the tunnel still runs through private land under the A386 roundabout.

His images and memories continued to Princetown past Burrator Halt with its remaining kissing gate, and the famous snake notice at Ingra Tor Halt. Back on the old main line, his views took us past the “black bridge†at Horrabridge and the stunning Walkham viaduct to the two stations at Tavistock. On to Lydford where the Southern and GWR stations sat side by side, sharing facilities such as the signal box.

This was a classic evening for showing the importance of recording local history because of how quickly things can change and be forgotten. Bernard’s stunning images taken over many years have done this superbly, also making for an excellent talk – all supplemented by his unique humour and off-the-cuff anecdotes.

On the road in Devon in 1682

Kevin Dickens painted a picture of life in the period of Restoration. Charles 11, the “Merry Monarch†with his many mistresses including Nell Gwyn was king and life on the surface seemed good, contrasting vividly with the time of Puritanism. Christmas had been restored, there was maypole dancing again, licentiousness and live theatre with racy comedies was popular. However, in the background people were haunted by bad memories – could the year of ’41 come again – the Civil War, religious disorder and dissention, the Popish Plot to overthrow the Government and the Rye House Plot where one of the Russell family was killed.

Kevin went on to take us on a journey of the time through Devon from Tiverton to Plymouth. He drew on tales from several notable travellers such as Tristan Risdon, Count Magalotti and Daniel Defoe. Roads were rough (maybe to slow any advancing armies); vehicles were primitive – “boxes on strapsâ€; inns were very basic often with mixed bedrooms, shared beds and risks of fleas and lice; the weather was not good either – 1675 was in the middle of a little ice age.

Tiverton was dominated by wool merchants with their smart houses, though the town had alms houses and the ruins of a fort. Dissenters’ bodies which had been hung, drawn and quartered were on display. Further down the road Barnstaple, a Parliamentary town in the Civil War, had been occupied by brutal Royalists who were now laying low nearby. Bideford had been a Civil War garrison and now the churches were centres of anger and dissention. Three poor women were accused of witchcraft and sent to Exeter Assizes. In Torrington, a Royalist (Cavalier) town, tensions were everywhere. Here, there had been street fighting with c200 people killed in a church explosion.

The town of Exeter was a powder keg. The Duke of Monmouth was welcomed that year in the town. Society was divided and tense between the gentry and the clergy, rich merchants and the poor. The three ladies from Bideford were found guilty and executed. Totnes was passed by quickly, then a town in decline.

Plymouth had survived a 3-year siege from the Royalists though had suffered c 3,000 deaths, a quarter of the population. Magalotti described it as sedition and now the King took charge. No parliaments were called, a standing army was formed, and foreign subsidies undermined the City of London. The fears of ’41 come again, resurfaced.

Three years later King Charles was dead, allegedly from self-inflicted but accidental mercury poisoning. Fears for the future returned and in 1688 William of Orange landed at Brixham to claim the throne from James 11. Wars with France followed though there were compromises on religion. Plymouth had a new dockyard.

Thanks to Kevin for a very informative and entertaining talk.

.